Future Arrangements

The design of Trinity Chapel’s worship space anticipated the future of liturgical architecture in the Anglican tradition in a number of different, and often contradictory ways. The use of stained glass windows, for example, was clearly a controversial move in the 1620’s to some Englishfolk. [48] Indeed, one of the members of Lincoln’s Inn in 1623 is known to have been involved in the smashing of stained Galss windows while taking part in an iconoclastic moment during the English Civil War. Yet it became a common practice in English churches after the Restoration; such windows are now regarded as part of the glory of English church architecture.[49]

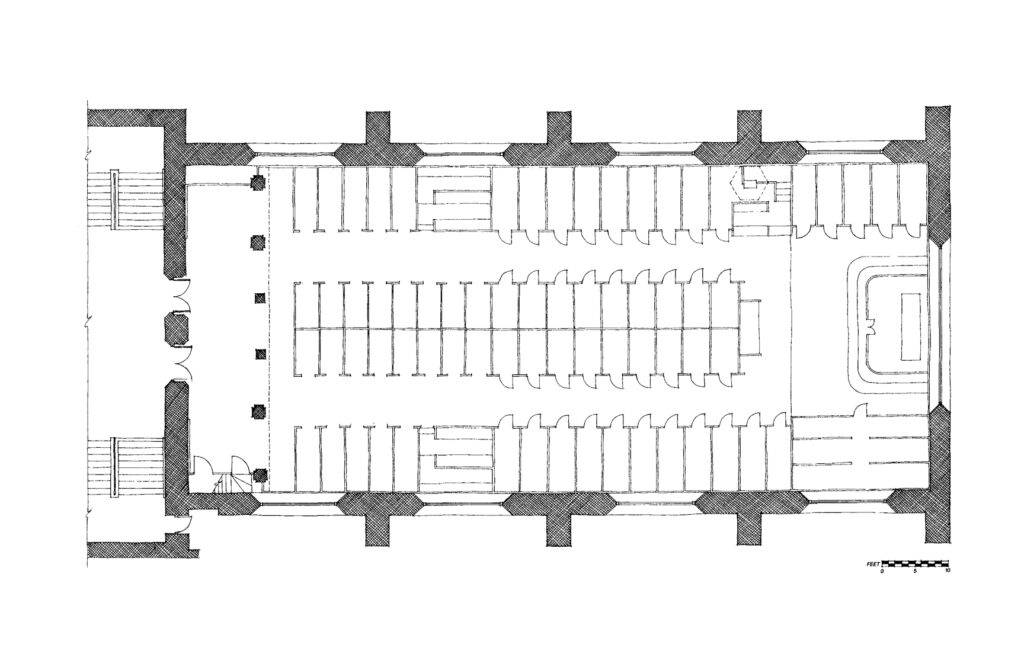

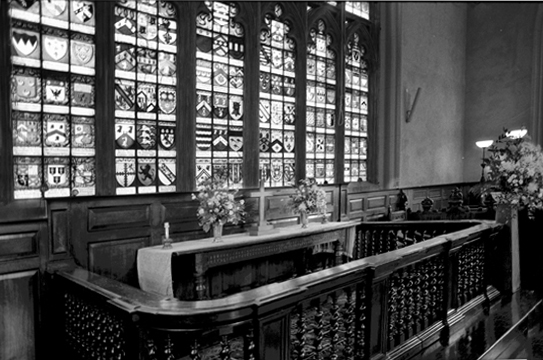

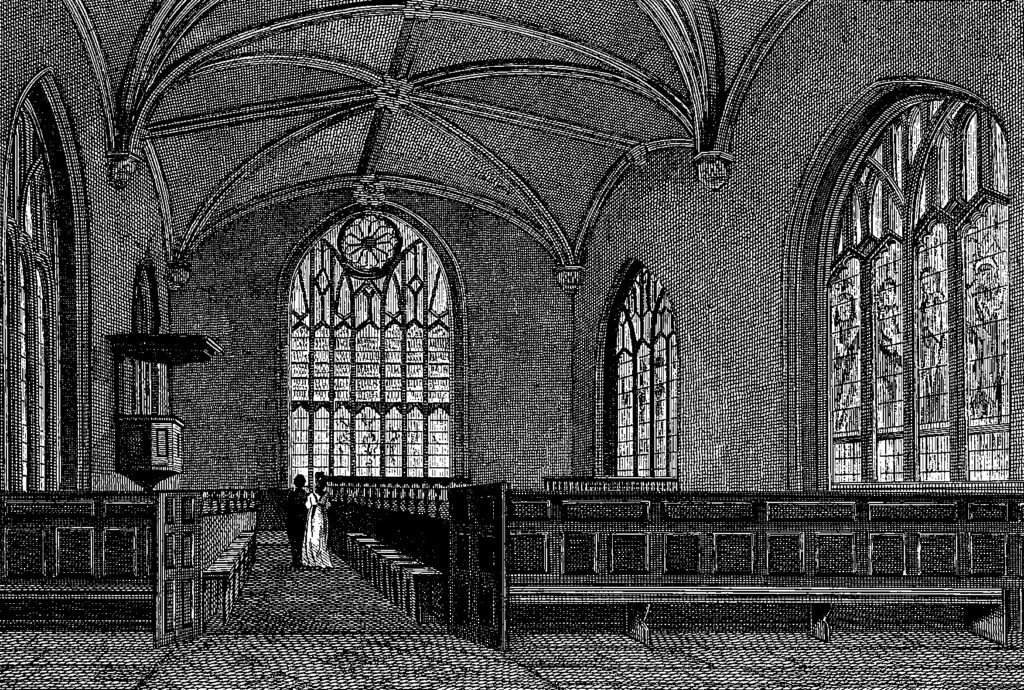

The floor plan of Trinity Chapel as it looks today reveals other changes in the arrangements of furniture and space that reflect changes in liturgical style. The altar, in 1623 located in Trinity Chapel in the middle of its own dedicated space, a seating area so that Bishop Montaigne faced members of the congregation across the holy table on the 22nd of May, is now of course relocated to a pre-Reformation location against the east wall of the building, surrounded by altar rails. Such a move was promoted by Laud and his supporters in the 1630’s and would, like the stained glass, prove controversial in the run-up to the Civil War. Again, like the use of stained glass, this became common practice after the Restoration.

One cannot be sure when this relocation of the altar took place in Trinity Chapel; it is against the east wall today, taking the place of the bench made for that space by Price the Joyner in 1623. That is also its location in every image we have been able to find of the inside of the Chapel, all of which show the eastward location of the altar from at least the middle of the 18th century.[50] Our best guess is that the relocation of the altar to the east end of Trinity Chapel was a post-Restoration development, taking place when the east end was remodeled in the late 17th century when the east wall had to be taken down and rebuilt due to structural defects in the original construction.

The location of the altar in Trinity Chapel in 1623 – and in English churches generally after the Reformation when medieval altars-against-the-wall were taken out of churches – of course is also anticipatory of future church practice, although we must wait until the Liturgical Movement of the 20th century and its recovery of patristic practice for altars to again become tables, for celebrants to again face their congregations across those tables, and for parishioners to receive communion gathered around the table instead of kneeling at a rail separating them from the clergy.[51]

The pulpit in Trinity Chapel has also moved; it stands today against the north wall, elevated above the seats (which remain in pretty much their original 17th century configuration) in a position that also achieved wide popularity in the late 17th and 18th centuries. Trinity Chapel’s pulpit today dates (according to Pensevier) from the early 18th century, when it must have replaced the original one. The central location of a pulpit, which persisted in reformed churches until very recently, though they stand near the east wall with no communion room behind them, seems in Donne’s day in England not to have been a sign of affiliation with any particular theological tradition, since the pulpit at St Katherine Cree church, beloved of Laud, also stood in the middle of the building at the top of the nave. [52]

The shift in altar and pulpit also meant the abandonment of the two-room model for the organization of liturgical space. But even the two-room model for the arrangement of liturgical space has had a come-back. Originally a way of accommodating medieval buildings for use of the Book of Common Prayer, this arrangement in Trinity Chapel achieves its own integrity in the creation of a room for the Word and a room for the Table, with movement from one to the other becoming a part of the liturgical action. After the Restoration, most English churches were reconfigured into a single room, with people remaining in their seats in the nave until time to come forward to receive communion. In at least one contemporary case – St Gregory of Nyssa’s Episcopal Church in San Francisco – a building constructed in the late 20th century replicates the arrangement of Trinity Chapel, with separate rooms for Word and Table.

Trinity Chapel as a liturgical space thus looked backward and forward, locating itself in the tradition of Prayer Book worship yet anticipating changes that were to come in that tradition. The extraordinary number of documents that survive from this building’s consecration record for us details of the way a significant number of Londoners spent their time on the morning of May 22, 1623 in and around Trinity Chapel on the grounds of Lincoln’s Inn and clarify dramatically features of worship in the Stuart church. As Judith Maltby has noted, so much of what we know about the ordinary use of the Book of Common Prayer comes to us negatively, as a result of court actions sought by parishioners to force their Puritan clergy to use the Church’s official liturgy.[53]

We now, however, have substantial positive evidence. The accounts of the Dedication service confirm the accuracy of Harrison’s account of English worship in his Description of England, that ordinary worship in parishes and chapels included, as the Book of Common Prayer directs, Morning Prayer, the Great Litany, and Holy Communion, with “a homily or sermon,” with Evening Prayer and another sermon in the afternoon.[54] To those attending the Dedication service at Trinity Chapel “between the hours of eight and eleven” on the morning of Thursday, May 22, 1623 who fulfilled their duty to record the event or who cared enough to set down what they saw and heard, and to those who have so diligently preserved this material over the years, we must be deeply grateful.

Thanks to them, we now see how the rites of the Book of Common Prayer were used in regularly-occurring worship and how they could be modified for special occasions. For a reconstruction of this service, go here. In this sesrvice, we can see how such adaptations could be done so as to fit seamlessly into the basic order of the Prayer Book liturgies, fulfilling the task of recognizing special circumstances while at the same time allowing the regular order of worship as envisioned by Cranmer to proceed. We also know much about how worship would be conducted, as in this case, when several clergy were in attendance, allotting leadership roles to at least three ordained people, with one serving as Minister for Morning Prayer and the Great Litany, one delivering the sermon, and another celebrating at the Eucharist. We have a clear example of how the three pieces of Divine Service on a Sunday or holy day were integrated with each other in actual performance.