The Exterior

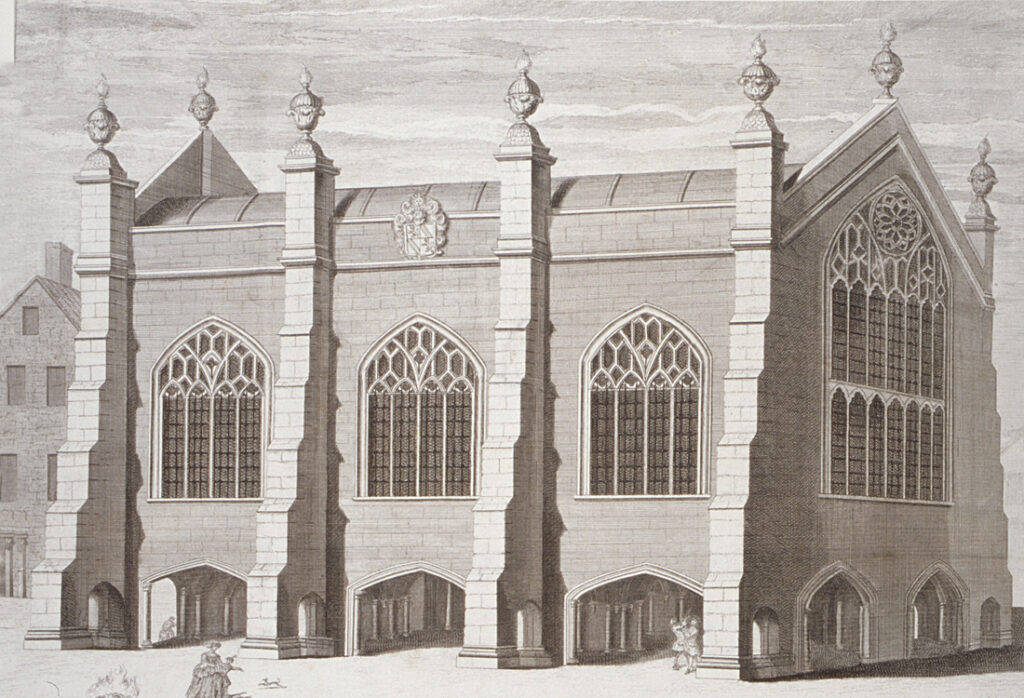

The exterior of Trinity Chapel — constructed in the early 1620’s — is best thought of as a Gothic survival building. In its use of external supporting pillars dividing the north and south walls into distinct bays, its ribbed vaulting and stone tracery, and its use of large windows with pointed arches in the walls and east and west fronts, Trinity Chapel reaches back to the late Middle Ages for its architectural inspiration.*

It does so at a time when, under the influence of Inigo Jones and others, the arcthitectural style of the Italian Renaissance was becoming the dominant style for new building designs in seventeenth-century London. See, for example, Jones’ design for the Queen’s Chapel, for which the foundation stone was laid in the spring of 1623, roughly the same time that Trinity Chapel was being consecrated.

Unlike so much of Donne’s London, Lincoln’s Inn and Trinity Chapel escaped the Great Fire of London. If one visits it today, the exterior of Trinity Chapel looks much as it did in 1623. The eastward three-fourths of the building are externally intact; the dramatic undercroft remains much as it was in 1623.

Only the west end – extended by about 25 feet in the late 19th century – differs significantly from the original design. The basic style of this extension closely matches the original on the north and south sides of the building, , though the building now has an additional bay of windows on each side and a more elaborate entranceway, with the west end enclosing the main entrance and incorporating a pair of staircases that replace the original design’s free-standing steps[14] leading up to a large doorway in the west end.

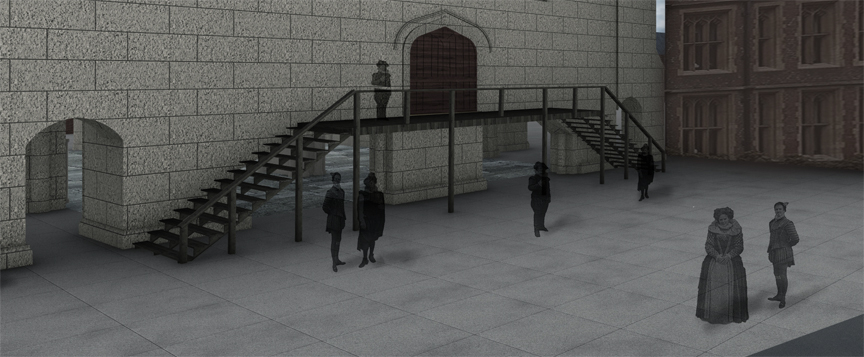

To our knowledge, no image of the Chapel’s West Front exists prior to the 19th century remodeling, so we have had to recreate it out of fragments of information.

These fragments include words from the Deed of Consecration prepared by Bishop Montaigne, to theeffect that on the morning of May 22nd, 1623, “The reverend father in Christ aforesaid, accompanied by many reverend and venerable men, approached the doorway of the chapel to be consecrated” where they were met by four Masters of the Inn.” So, we glean that the Chapel had a main doorway, with a landing outside of it large enough for eight or ten men to meet and transact the ceremony of the representatives of Lincoln’s Inn giving over to the Bishop of the Diocese their ownership of the building.

Given the fact that the interior of the Chapel rests on the stonework of the undercroft, the doorway to it also had to be several feet above ground, requiring flights of steps to reach it from ground level.

An image of a large doorway survives, labeled “Lincolns Inn Chapel Doorway of,” an attestation we have accepted. We also know that the original steps leading up to this doorway were demolished within about a year or so of the Consecration and replaced with a set of brick steps. We have agreed to show the West Front having the original wooden steps and landing, to replicate the arrangements on the day of the Consecration Service.

Today’s West Front looks quite different. The remodeling of Trinity Chapel in the 19th century included adding to the extended West Front two sets of stairs — one on the north and the other on the south — fronted by a two-story stair tower that draws on architectural features of the original structure, including the butresses on either side of the central archway.

*Episcopalians will be interested to learn that the basic design of Trinity Chapel made its way across the Atlantic in the 17th century, reflected in the design of early parish churches in Tidewater Virginia, such as St Luke’s, Smithfield, Virginia.