The Interior

The interior of Trinity Chapel in 1623 reminds us that it was purpose-built to express physically the liturgical principles implicit in the Books of Common Prayer of 1552 and 1559. In the service of Holy Communion, the rubrics call for use of a “table, havyng at the Communion tyme a fayre whyte linnen cloth upon it,” that “shall stand in the body of the churche or in the chauncell where mornyng prayer and evenyng prayour be appointed to be sayd.” The priest celebrating Holy Communion is instructed to stand “at the Northe syde of the table.”

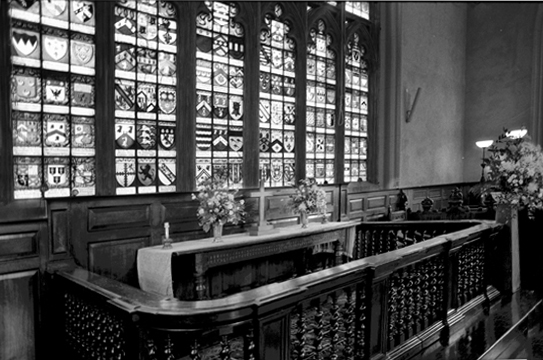

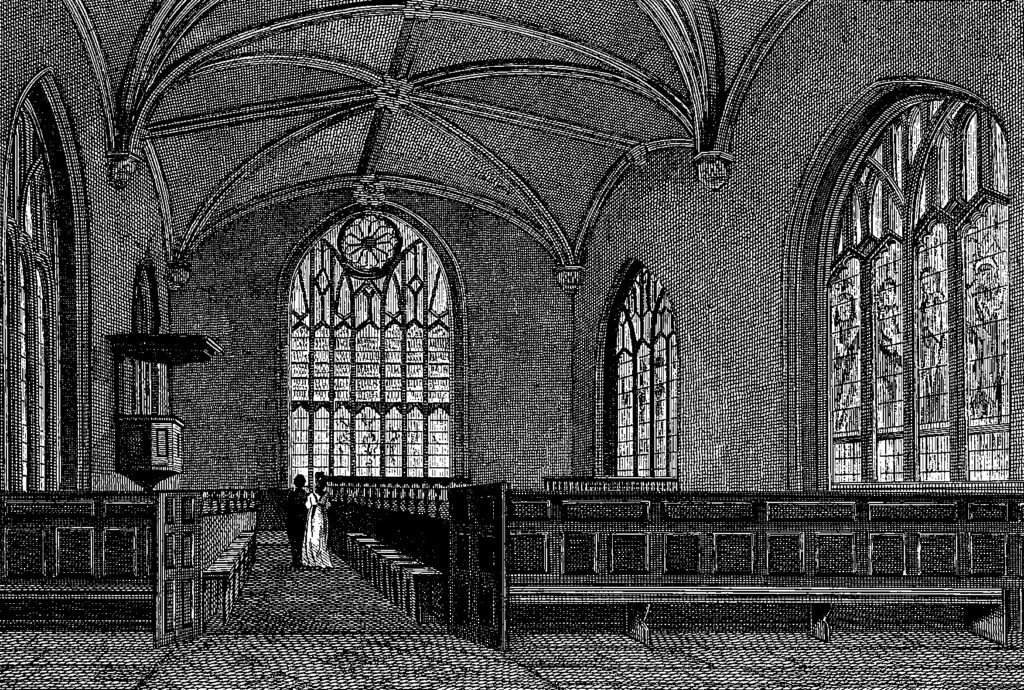

The interior of Trinity Chapel today reflects a very familiar Anglican arrangement of space, an open room filled with banks of pews facing eastward, with a pulpit on the north wall about two-thirds of the way from the west end toward the east wall and with an altar against the east wall, railed in and joined in the east end of the building by banks of seats flanking the altar, one on the south wall and one on the north wall.

The altar in today’s Trinity Chapel is against the east wall. Although it is still a table, not a stone altar, it is clearly designed so that the priest stands facing the east wall, with his back to the congregation.

In today’s Trinity Chapel, the space is treated by its users as a single room in which the congregation sits in the eastward-facing pews for the entire service, while the clergy, attendant servers, singers, and others responsible for leading worship sit in the seats near the altar. The congregation remains in the west end throughout the service, leaving their pews only to approach the altar to receive the bread and wine of communion.

The original layout of the Chapel was different in some basic ways, as Price the Joyner’s bill for carpentry, submitted to the Inn in June of 1623, helps us understand. This list specifies the furniture included in the original design and indicates where each piece of furniture was to stand, often in places where other items now stand. Especially in its reference to a “long Pew in the Chancell being put Close to the wall” where the altar now stands, to the “pulpit that standes in the midst of the chappell in the upper part of the Chappell” as opposed to its standing against the north wall, and to the “Communion table” with “bordes under the Communion table”[15] — reflects a very different organization and understanding of liturgical space.

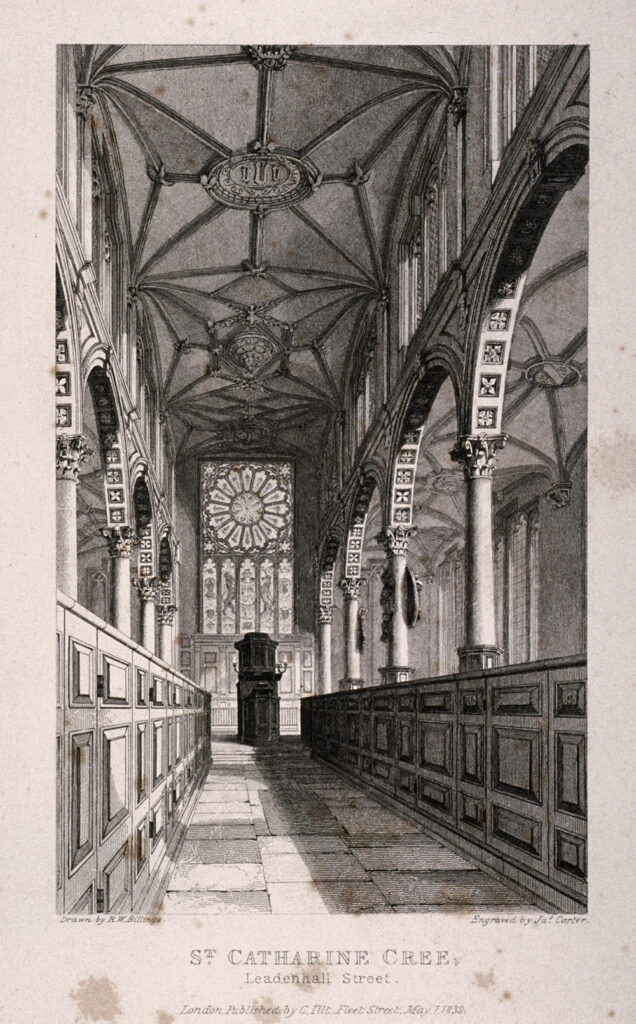

Our decision to take Hugh Price seriously about the pulpit’s being “in the midst of the chappell” was encouraged by our discovery that another example of new church construction in London in the early seventeenth century , St Katherine Cree, where, as this engraving shows, the pulpit was also located in the “midst” of the church. St Katherine Cree was consecrated in 1631 by William Laud, who was then Bishop of London.

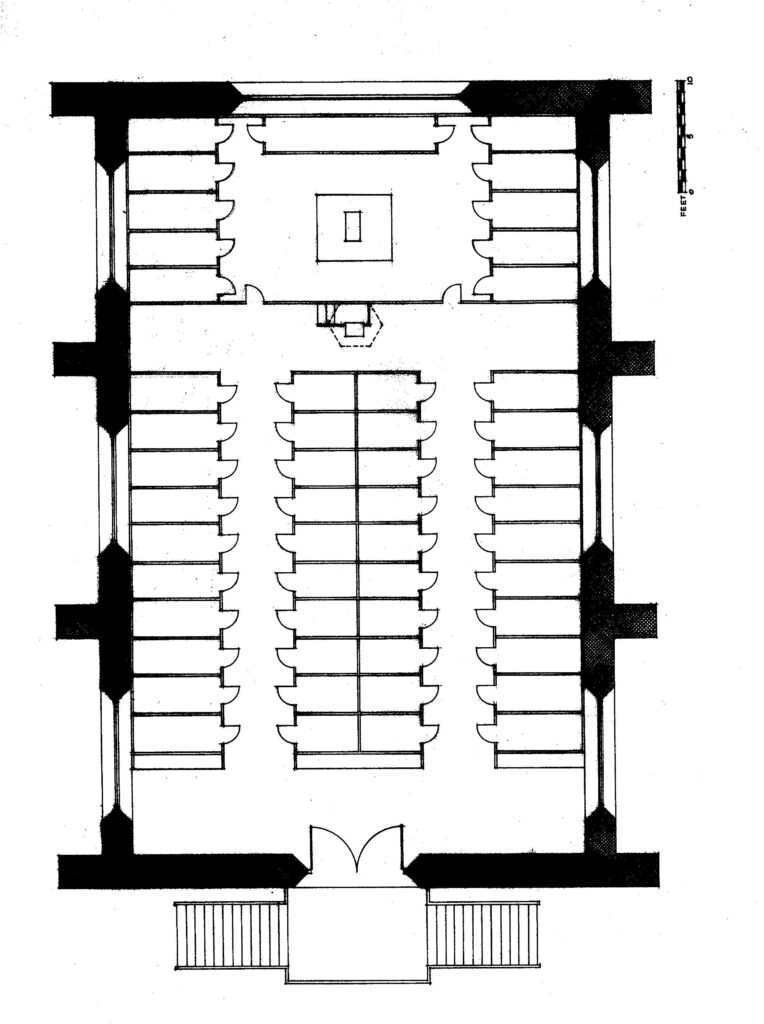

This information helps us understand that in 1623, the interior of Trinity Chapel was divided by the architecture and the arrangement of furniture into two distinct spaces, with the demarcation marked physically by the 4-inch “step” one ascends in moving from one space to the other and reinforced by the organization of the pews, with those in the nave pointing eastward and those in the chancel pointing westward.

The westward room constitutes a room for reading, preaching, and prayer, while the eastward room provides a room for celebration of the Eucharist, with the Communion Table placed in close proximity to the seats in the quire/chancel, leaving room for the Celebrant to stand on the north side of the altar and for the people to gather around the altar and kneel to receive the Communion, but still close enough to the seats in the Choir for the officials of the Inn to feel they needed to ban people sitting in that area of the Chapel from placing “their handes or armes or any other partes of their bodies,” not to mention their “hattes or bookes” on the altar itself.

This two-room design reflects a continuation of ways in which the reformed Church of England adapted medieval church buildings in the 16th century for use of the Book of Common Prayer. All altars were removed from medieval church buildings; a table set up in the chancel served as the altar for the entire congregation. People participated in Morning Prayer and the Great Litany in the nave, then moved to the chancel for celebrations of Holy Communion.

In Trinity Chapel, the nave occupied the western two-thirds of the building, holding most of the pews and the pulpit, while the eastward third of the building, referred to as the “chancel” or “quire” in the Inn’s documents, was used for celebration of Holy Communion, with an altar/table in the center of this space, surrounded by banks of pews on the north and south sides and by the “long Pew” against the east wall.[18] While Trinity Chapel is, from the outside, a building medieval in appearance, with its continuation of gothic architectural design and its use of stained glass windows, instead of a neoclassical building at this time coming into vogue through the influence of Inigo Jones and others.[19] Internally, however, it is organized according to advanced liturgical principles for accommodating use of the Book of Common Prayer to medieval church spaces.

The point at which the furniture inside Trinity Chapel was rearranged into its current configuration is unclear. The image above from 1804, which shows the Chapel’s interior in essentially its current arrangement, gives us a definite point in time by which the work had been done. Nikolaus Pevsner provides us with another clue in his London North volume in Penguin Buildings of England series (1998). Pevsner says that the current pulpit is an example of “Charming early 18th century work,” thus definitely not the pulpit built in 1623 by Hugh Price but perhaps the pulpit shown in the image from 1804. We do know that the east end of Trinity Chapel fell into disrepair at the end of the seventeenth century and underwent major repair, supervised by, of all people, ChristopherWren, so perhaps the Masters of Lincoln’s Inn chose that occasion to rearrange the furniture into what was by then a customary pattern in English churches.

The Windows

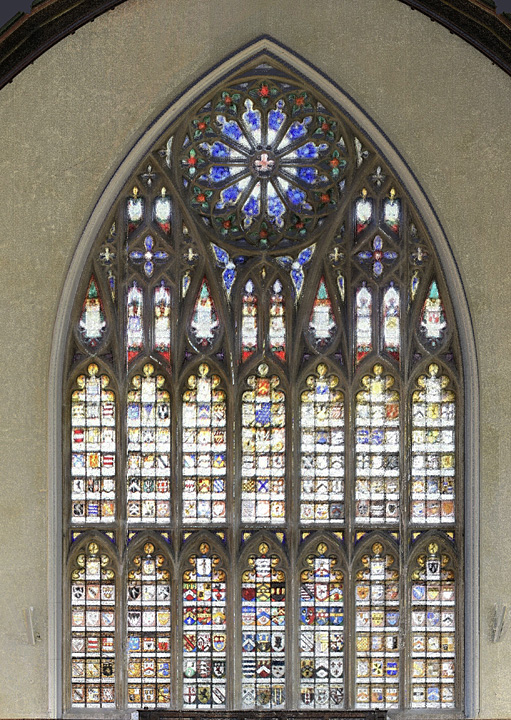

Trinity Chapel, in 1623, had a program of stained glass which included eight large windows, three on each side of the Chapel and one on each end. The window on the East Front was reserved for use as a fundraising site, with members of the Inn paying fees to have their coats of arms included in the window. As of now, this window seems to be completed filled, but we have left it mostly clear in anticipation of future needs by members to record their presence.

The windows on the north and south sides of the Chapel each had 4 glass panels, allowing for four figures to be included in each window. The three windows on the north side displayed images of ten characters from the Old Testament and two from the New Testament; the three windows on the south side of the Chapel contained the figures of Jesus’ twelve disciples.

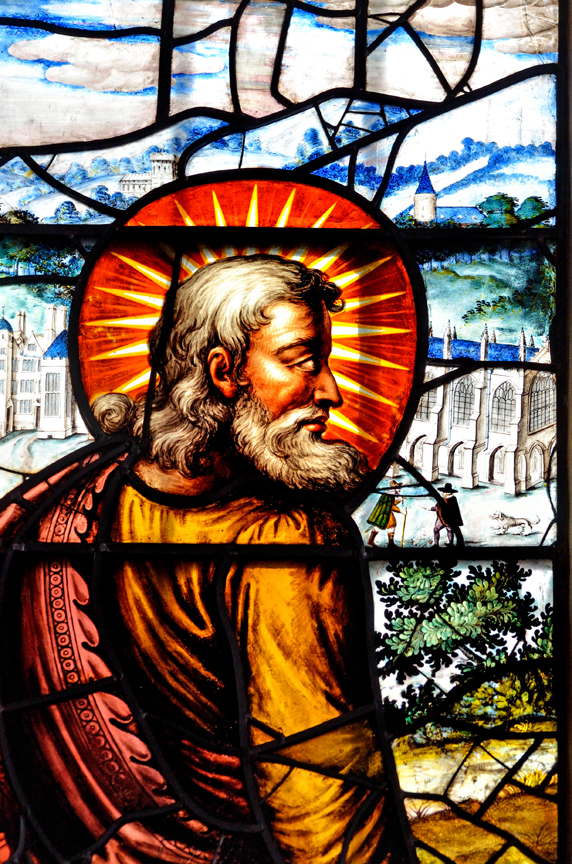

The windows on the north side of the Chapel were created by Richard Butler, a London-based stained glass maker; the windows on the south side were the work of Bernard and Abraham van Linge, brothers from Holland, who spent most of their career as makers of stained glass in England. In today’s Trinity Chapel, four of the original six survive.

Work of the van Linge brothers can be sampled here:

Seating

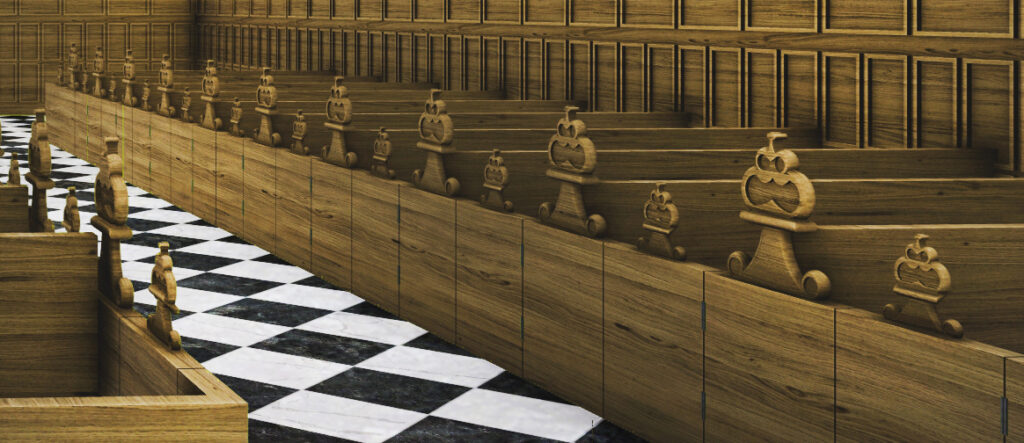

Even though the pulpit and altar have moved within Trinity Chapel since 1623,[20] the seating has remained essentially the same. There are two exceptions, the first being the addition of pews westward to provide seating in the area of the Chapel added by the extension of the building in the 19th century. These seats are quickly distinguishable from the original pews because the original seating is enclosed, with doors in the sides providing access to the seating from the aisles. The new seating lacks the doors and the ornamental pediments atop framing around the pews. The other exception is in the Chancel area, where the pews on the south side which originally faced westward now face northward.

In part, this conservatism in regard to the seating is due to the fact that the original plan of seating approved by the governing body of Lincoln’s Inn on 13 May 1623 allocates seating throughout the Chapel to specific groups of people who were members of the Inn community, according to status within that community. Thus, for example, we read in the Black Books:

The two first double seates next the Quire to be set apart and allottetd to such Nooblemen, Judges, Serjeants at Law, and other persons of eminent quality, as shall att any tyme resort and repaire to the Chappelle. The six next double seates there to be for the Masters of the Bench and the Associates, and they to place themselves by three and three in every one of them, accordinge to their antiquity.[21]

And so forth, throughout the building, with similar kinds of specific assignments for the various constituencies of the Lincoln’s Inn community, with specific places set aside for the clergy of the Inn on the north side of the Choir. According to this document, the area “from the Quire downward” contained ten rows of pews with a double row down the center of the building and single rows of pews on each side wall. In the current building, in regard to seating, the eastern 2/3rds of the building, corresponding to the footprint of the original structure, has pews in exactly this arrangement; older pews can be distinguished from pews in the westward addition to the building by the fact that the older pews have doors while the newer ones do not.

According to the bill from Price the Joyner, the original building had a “long pew in the Chancell, being put close to the wall.” Given the confirmed sites of the five rows of pews on the north and south sides of the Chancel, or choir, the only place remaining for a “long pew” to be “put close to the wall” is along the east wall, where we have placed a pew in length equal to the pews that run down the middle of the Chapel. We have located the pulpit “in the middest of the chappell in the upper part of the Chappell,” though keeping it in the nave area because trying to put it in the Choir area seems crowded and also confuses the use of space in a way that is out of keeping with the careful articulation of spaces according to liturgical function characteristic of the rest of the building.

The nine pews on the north side of the nave provide seating for 36 to 45 additional persons; the seating in the “quire” provided for an additional ten pews less the two assigned to the Preacher and the Reader, making eight pews of a 4- to 5-person capacity plus the 6 persons who could occupy the “long pew,” for a total seating capacity of 40 to 48 in the “quire.” Thus the regular seating capacity of Trinity Chapel was 146 to 164 persons, plus the seating—perhaps sufficient for another 10 to 15 people—provided for “the clarkes and ordinary servants . . . and of the servants of the Howse” by the benches kept at the back of the pews in the nave.

In other words, on a typical Sunday or Holy Day, when a sermon was preached, the preacher faced a congregation of perhaps as many as 175 people if everyone was present who could be accommodated in Trinity Chapel. On 22 May 1623, however, as we know, the occasion was of sufficient significance and interest to draw, according to Chamberlain, “great concourse of noblemen and gentlemen wherof two or three where indaungered and taken up dead for the time with the extreme presse and thronging.” [22]

So the Chapel on this day was packed; whether the members of the Inn were able to take their appropriate and assigned seats amidst the crowd of visitors is uncertain. We may be confident, however, that Donne had a full house to hear his sermon, occupying all the seats both in the nave and the “quire,” and presumably standing perhaps several persons deep along the back wall.