The Service on Ascension Day, May 22nd, 1623

The service of worship conducted in Trinity Chapel on May 22, 1923 was the service of consecration, or dedication, as Donne labels it in his sermon, the first service conducted in this space, a new space just completed for the use of members of Lincoln’s Inn. The Black Books of Lincoln’s Inn show that the Inn had been planning for this day for several years. Donne preached at this service because he had been involved in the project since early in his tenure as Reader, or Preacher, at the Inn. He went to work there in 1616 and remained in this position — except ofor his time as Chaplain to until he became Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral in 1621. His activities in support of the building of Trinity Chapel included preaching a sermon at the Inn, in 1618 or 1619,specifically to support the residents of the Inn in “preparing . . . to build their Chapel.”[8] He also, according to his own testimony, laid the first stone of the Chapel “with [his] own hands.”[9] In addition, he contributed to the cost of one of the stained glass windows, a fact which to this day is recorded in the window itself .[10] The Inn’s leadership, perhaps in appreciation for his active role in the construction of Trinity Chapel, invited Donne back from his work as Dean of St. Paul’s to preach the sermon at the service of dedication and consecration for this building on 22 May 1623.[11]

The inaugural service of worship at Trinity Chapel on May 22, 1623 was, as one would expect, the ordinary service for a Sunday or Holy Day, that is, Morning Prayer, followed with the Great Litany, followed by Holy Communion, according to the Book of Common Prayer (1604) and the Canons of the Church of England. On this day, however, Divine Service was augmented by a bit more ceremonial and special prayers and other texts prepared for this occasion, which, together with the inauguration of regular worship in the space of Trinity Chapel, constitute a service of Consecration, or in the language of the Inn’s own account, the “blessing and preparation for use” of this new place of worship.

This was of course necessitated by the fact that the Book of Common Prayer contains no service of consecration, a consequence, perhaps, of Thomas Cranmer’s desire to shift concepts of holiness away from things, such as consecrated bread and wine, relics of the saints, holy sites, and other objects of devotion in medieval spiritual life, and toward people, toward perhaps “the blessed company of all faithful people,” the coming-to-awareness of which is the goal of his Eucharistic rite in the 1552 Book of Common Prayer.

While some reformers in the early years of the English Reformation, such as Nicholas Ridley, who referred to the act of blessing material objects as “conjuring,” had rejected the blessing of objects, by the late 1500’s and early 1600’s some dioceses of the Church of England had recognized the value of consecrations, perhaps to coincide with a time of renewed church renovation and construction after years of adapting medieval buildings to the liturgical requirements of the Church of England. [23] The development of such rites of consecration reflects a “settling-in” of the reformed Church of England, a move from a time of reaction, when anything that could be viewed as too “Catholic” was likely to be scorned by enthusiasts for change, to a time of consolidating a new self-identity, when the needs of a community for liturgical expression of its defining occasions could be affirmed and supported.

Richard Hooker, as is so often the case, seems to reflect this development when, in Chapter 12 of Book V of the Lawes of Ecclesiasticall Politie, published in 1597, he argues that while the church properly considered is the people and not the building, nevertheless the consecration of a church building is not “in it selfe either vaine, or superstitious,” but an action intended “to surrender up that right which otherwise theire founders might have in them, and to make God him selfe theire owner.” We will see shortly how John Donne, in his sermon preached at Trinity Chapel during this consecration ceremony, echoes Hooker’s language about the purpose of consecration and the relationship between the building being consecrated and the people who have built it and who intend to worship within it.

Legg’s study of similar rites documents the consecration of at least 56 church buildings or churchyards from 1600 until the outbreak of the Civil War. A survey of these rites in Legg’s anthology helps us see this period as a time of experimentation in the development of a consecration rite for the Church of England.[24] Different bishops produced different rites; some included multiple services from the Book of Common Prayer, not just those constituting the ordinary practice of Divine Service.[25] Some included consecration of specific items of liturgical vessels and furniture; others like Bishop Montaigne choose to refer sweepingly to Trinity Chapel’s being “sufficiently and suitably decorated and fitted out with sacred table, pulpit, suitable seats, even a bell.”

What is consistent with all the 17th century rites is a number of common elements. At Lincoln’s Inn, as at other places, a bishop was the consecrating officer. These rites started with a ceremony of what Legg calls “the surrender of the building,” followed by the Bishop’s entry into the building alone, for prayer, before declaring the building open for the congregation to enter. These services also included rites from the Book of Common Prayer, always including a celebration of the Eucharist.[26] There also seems to be a pattern of locating the sermon on these occasions not, as the rubrics of the Book of Common Prayer specify, after the Nicene Creed in the Communion service, but after the Great Litany, a pattern followed by Bishop Montaigne at Trinity Chapel.

Otherwise, rites from the early 17th century show significant variation. The ceremony at Trinity Chapel, however, did follow precedent, although not unreflectively. Jeffrey Johnson has helpfully located the model for the liturgical text used at Trinity Chapel as the rite used by William Barlow, Bishop of Rochester, for the consecration of a private chapel at Langley, in Kent, on Sunday, July 26, 1607.[27] The opening sentences of both rites are the same (drawn from Psalm 122), except that at Trinity Chapel an additional verse – 2 Chronicles 7:16 – was added. The opening prayer of the bishops is essentially the same, although at Trinity Chapel the words “celebrating the sacrament of the Lords Supper” were substituted for Bishop Barlow’s “celebrating thy sacraments,” since Trinity Chapel was a chapel for a community of adult males and not their families. The Trinity Chapel rite adds declarations by Bishop Montaigne specific to the occasion, but the Psalms and Lessons appointed for Morning Prayer are the same, as are the prayer to be inserted after the prayer for bishops and curates in the Great Litany, the Collect and the Lessons appointed for the Eucharist, and the concluding prayer and address to the congregation, again suitably adapted for this occasion by Bishop Montaigne.

The Lincoln’s Inn manuscripts we offer here fill out the texts of the rite with specific details about how the ceremony was conducted. We are told by the Consecration manuscript that at 8:00 am on the 22nd of May the “reverend father in Christ” [George Montaigne, Bishop of London], accompanied by members of his staff, was met at the doorway of Trinity Chapel by Thomas Spenser, Richard Digges, Egidius Tooker, and William Ravenscroft, as well as by other members of the Inn, who indicated that they had, for the everlasting honor and service of God almighty, and the use of those staying in the aforesaid Inn, seen to the erection and equipment of the said chapel, on their own private grounds and with their own private funds . . . [a]nd they yielded their rights in the same, and so in their own names as also in the names of all others having an interest in this area, unanimous in agreement and consent, they granted, gave, and donated the aforesaid chapel to God almighty and to the highest, holy, and indivisible Trinity, and in token of a free donation of this sort, they presented and handed over the keys[28] of the aforesaid chapel to the same reverend, humbly beseeching the said reverend father to declare and consecrate the aforesaid chapel to the everlasting honor and service of God almighty, and the use of those staying in the aforesaid Inn.[29]

Bishop Montaigne then entered Trinity Chapel alone, though we are told that the assembly stood outside and looked in through the doorway, while the Bishop quoted from the Psalm 122 and 2 Chronicles, as noted above. He then, “moving forward a little,” knelt down and prayed “on bent knees and with hands lifted to the sky towards the east” that God “accept [this building] graciously at our hands, bless it with happy success,[30] and . . . give a blessing to thy holy word and Sacrament so oft as thy servants shall be here partakers of them.”

Bishop Montaigne then turned “towards the congregation still standing at the doors of the chapel” and read an extended “schedule of dedication and consecration” handed to him by Sir Henry Martin, his vicar general, to the effect that, with due respect for the rights and interests of neighboring parish churches, he had “separated from every common and profane use this chapel,” and had granted “license and right in the Lord, on our own behalf and that of our successors, for divine service to be conducted in the aforesaid chapel, to wit: recitation of public prayers and the holy liturgy of the Anglican church; the faithful propagation and preaching of the word of God, and the administration of the sacrament of the holy Eucharist, or supper of the Lord, in the same chapel.”

At the end of this declaration, the congregation who had gathered outside the Chapel were finally admitted to the space, and “regular prayers” were read by Thomas Wilson, one of Bishop Montaigne’s chaplains. Services proceeded according to the Book of Common Prayer, with its familiar prayers, versicles and responses, and Cantlcles, except, we are told, that some of the Lectionary readings for the day were changed for the occasion, such as the substitution of Psalms 24, 27, and 84 for the Psalms appointed for the day, and the substitution of 2 Chronicles 6 for the First Lesson and John 10: 22-42 for the Second Lesson. A Collect asking that God “accept this our day’s duty and service of dedicating this Chappell . . . and fulfill . . . thy gracious promises that whatsoever prayers in this sacred place . . . may be favorably accepted and returned with their desired success” was added to the Great Litany “after that collect in the Litany for Bishops and Curates.”

Donne’s Sermon

The Great Litany was, we are told, “followed by Psalm 23, which was sung,”[31] and which led to the sermon by “the reverend and venerable man Master John Donne . . . who for his theme read from chapter 10 of the Gospel according to John, verses 22 and 23.”[32] This position for the sermon, as we have seen, departs from the rubrics of the Book of Common Prayer which specify a sermon only in the Communion service, after the recitation of the Creed. The flexibility shown here by Bishop Barlow, and by the Bishop of London and his staff after him, in their rearrangement of the order of the parts of a typical Sunday or Holy Day service is both highly appropriate and a sign of the comfort bishops, clergy, and their congregations felt both in using the Prayer Book services and also in modifying their structure when specific, special, occasions called for variation.[33]

Donne gave his sermon on this occasion the title Encaeni,[34] “commencement” or “dedication,” in its printed version; in it, Donne makes clear that his subject is “dedication” in both its meaning specific to this occasion and its more general sense as a way of understanding a life committed to particular goals and values; he also makes clear that he is there, at Trinity Chapel, both to participate in this service of consecration (by preaching the sermon) and to comment on the significance of the service (through the content of this sermon).

Donne begins this sermon by offering a prayer containing a petition that links the Feast of the Ascension to the events of the day, asking that “as this day wee celebrate his ascension to thee bee pleased to accept our endeavour of conforming our selves to his patterne in raysing this place for our ascension to him.” His text is John 10:22, from the Second Lesson used at Morning Prayer for this occasion, “And it was at Ierusalem the Feast of the Dedication and it was winter and Iesus walked in the Temple in Salomons Porch.” His choice of text grounds his sermon in the specific liturgical occasion in which it is preached, first, because it is a text that was just read as a Lesson a few moments before Donne announced it as his text, and second, because this passage is soon to be referred to again in the Collect to be read after Donne’s sermon, at the beginning of the Service of Holy Communion, when Bishop Montaigne will say, “Must mercifull Saviour, which by thy bodily presence at the feat of Dedication didst approve and honour such devout and religious services as this we have now performed, present thyself also unto us by thy holy spirit.”

Even as Donne is aware of the relationship between the occasion – the opening of Trinity Chapel for worship – and the liturgical event which consecrates the building and thus sets it apart from a common to a holy purpose, so too is he aware of the relationship between the church as congregation and the church as building. Preaching to the persons gathered for the ceremony in and by which the new chapel will be set apart for a holy purpose, Donne addresses his audience’s sense of ownership in terms that echo Hooker’s claims for this relationship. Donne quotes St. Bernard, to the effect that “Nostra festivitas haec est, quia de Ecclesia nostra,” or, literally, “This is our festival because this is our Church.” Donne translates this phrase with a slightly different emphasis: “This Festivall belongs to us, because it is the consecration of that place, which is ours.”[35] He moves quickly, however, from an emphasis on the consecration of the place to the function of the place, from the building being consecrated to the consecration of the lives of the persons responsible for its construction, who properly, Donne says, are the focus of the occasion, since the purpose of the building is the consecration of its worshippers to God’s service:

These walles are holy, because the Saints of God meet here within these walls to glorifie him. But yet these places are not onely consecrated and sanctified by your coming; but to be sanctified also for your coming; that so, as the Congregation sanctifies the place, the place may sanctifie the Congregation too. Thus in his view, Sundays and holy days are “elemented of Ceremonie, but they are animated by Moralitie.”

Donne spends the first two-thirds of this sermon exploring the significance of the service itself, defending it both against a potential Catholic charge that the Church of England is deficient in its ceremonies and a potential Puritan charge that holy days and their ceremonies are unbiblical and therefore inappropriate, asserting that “They who disdaine not the name of sonnes of the Church, refuse not to celebrate the daies, which are of the Churches institution.” Along the way, he defines the practice of the Church of England over against the worship practices of Jews, Catholics, Lutherans, and Calvinists, as well as affirming the division of worshippers into clergy and lay, and by extension the transfer of the title of Trinity Chapel from its lay owners to the Church, in the person of “This servant of God, the Right Reverend Father the Bishop of this See.” Here we need to remember that Donne is performing this effort to interrelate differences precisely in relationship to his congregation’s sense of possession, of ownership, of what is “ours” and what is not, and, ultimately, of what constitutes and forms holiness, what makes something holy. The congregation gathered before Donne on this day in May 1623 had reason to be proud of what they had brought forth. Donne makes special note of the effort it took on the part of the Lincoln’s Inn community to build this Chapel; drawing a comparison between the widow who gave her mite and the funding of the Chapel, Donne notes:

I, I say, can truly testifie, that . . . you gave more then the widow, who gave all, for you gave more then all . . . strangers shall not know, how ill we were provided for such a work, when we begun it, nor with what difficulties we have wrestled in the way; but strangers shall know to God’s glory, that you have perfected a work of full three times as much charge, as you proposed for it at the beginning.

In the end, however, he returns to his earlier theme of the relationship between buildings and people, between the dedication of this Chapel building to God and the dedication of “ourselves to God” by renewing “in our selves the Image of God, and put off the Olde man, and put on the Lord Iesus Christ.” For this “is truly Encaeniare, to dedicate, to renew our selves.

Holy Communion

When Donne concluded his sermon, we are told, Bishop Montaigne “prepared himself[36] for celebrating the Eucharist, with the worshipful and venerable lords summoned together along with some other counselors[37] of the aforesaid Inn then present in the same place before the altar.” The language here indicates that conventional practice regarding Communion was functioning here; that is to say, “some” participated, but not all. Those participating would have come forward into the Choir area of the building, joining Bishop Montaigne around the altar for After the Communion service, Bishop Montaigne “added this thanksgiving for finale, and in a deep voice pronounced, to wit:

Blessed be thy name, O Lord our God for that it pleaseth thee to have thine habitation among men, and to dwell in the assembly of the righteous. Bless we beseech thee this day’s action unto us, prosper thou the work of our hands upon us, Lord prosper those our handy work, bless this house [and family] and the owners thereof into whose minds thou diddest putt it to have this place consecrated unto thee, Be with them and theirs in their going out and coming in and make them truly thankful unto thy glorious name, who being so great a God and the Lord of the whole earth, vouchsafeth to accept these poor offerings from sinful men which are themselves but earth and ashes And grant that they and their successors may faithfully serve thee in this place to the comfort of their own souls and the everlasting praise of thyglorious Majesty, through Jesus Christ our Lord and only Savior. [Amen.]

Bishop Montaigne then called the leadership of Lincoln’s Inn forward to face the altar and addressed them to the effect that he had done as they requested, in consecrating “this place”; he then charged them to use “this place” rightly not to “do or suffer to be done any thing contrary to that is now intended and performed.”

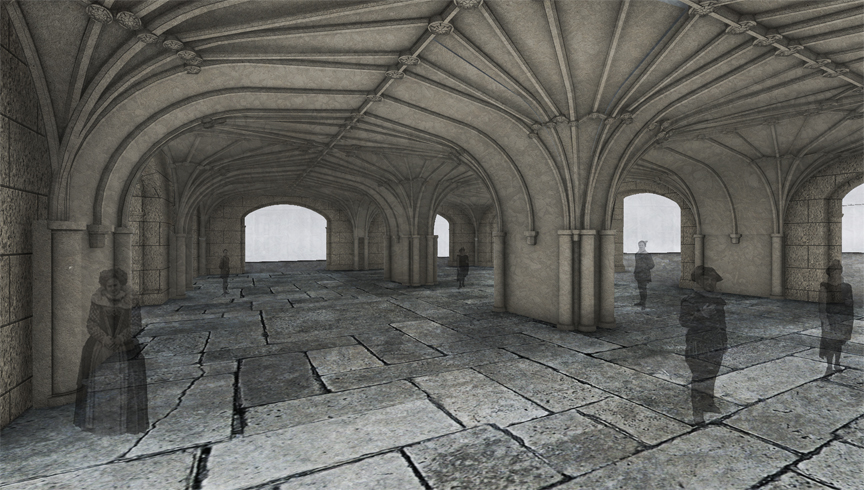

After they had assented to this charge, Bishop Montaigne dismissed the congregation and everyone went outside, through the west door, and down the steps to the undercroft, where – since this space was intended to be used as a burial ground for members of the inn, Bishop Montaigne went through a blessing and hallowing of that ground. He and his party circled the ground to be consecrated; then Bishop Montaigne sat down on a seat provided for him “and fittingly decked out, and in the same place rested himself for a little while.” [38] He then read a long statement dedicating this space to be “a cemetery or place of burial of dead bodies in and for the aforesaid Inn . . . to be secured with the privileges, all and sundry, customary and requisite for cemeteries or consecrated places of this sort, eligible by law, to the full effect of the law, and so far as is in us and we are able by law, we so fortify and stabilize (it) according to the intention of those present.” Bishop Montaigne then “made prayers for the blessing of the aforesaid work,” blessed the assembled throng, and dismissed them “with that Apostolic benediction, to wit, The peace of God which passeth all understandinge etc,” and everyone who was a member of the Inn, as well as those who had performed the Service of Consecration, retired to the Great Hall of the Inn, next door to Trinity Chapel, for a celebratory dinner.

The Consecration service for Trinity Chapel in 1623 thus clarifies for us the way in which regular worship occurred in chapels, cathedrals, and parish churches in the post-Reformation period. The accounts of the Dedication service confirm the accuracy of Harrison’s account of English worship in his Description of England, that ordinary worship in parishes and chapels included, as the Book of Common Prayer directs, Morning Prayer, the Great Litany, and Holy Communion, with “a homily or sermon,” with Evening Prayer and another sermon in the afternoon.[1]

To those attending the Dedication service at Trinity Chapel “between the hours of eight and eleven” on the morning of Thursday, May 22, 1623 who fulfilled their duty to record the event or who cared enough to set down what they saw and heard, and to those who have so diligently preserved this material over the years, we must be deeply grateful.

Thanks to them, we now see how the rites of the Book of Common Prayer were used in regularly-occurring worship and how they could be modified for special occasions. We see how such adaptations could be done so as to fit seamlessly into the basic order of the Prayer Book liturgies, fulfilling the task of recognizing special circumstances while at the same time allowing the regular order of worship as envisioned by Cranmer to proceed. We also know much about how worship would be conducted, as in this case, when several clergy were in attendance, allotting leadership roles to at least three ordained people, with one serving as Minister for Morning Prayer and the Great Litany, one delivering the sermon, and another celebrating at the Eucharist. We have a clear example of how the three pieces of Divine Service on a Sunday or holy day were integrated with each other in actual performance.

[1] Harrison, p. 34.