Framework: Worship at Trinity Chapel, Lincoln’s Inn, London, May 22, 1623

The worship service conducted in Trinity Chapel at London’s Lincoln’s Inn “between the hours of eight and eleven” on the morning of Thursday, May 22, 1623, turns out to be one of the most thoroughly documented worship service held in England between the Elizabethan Settlement of Religion and the outbreak of the English Civil War.[1] Unique for this event, we have visual evidence as well as numerous written records, both official and unofficial, which together enable us to learn in great detail what Trinity Chapel looked like in its original configuration as well as what happened during this worship service inaugurating religious use of Lincoln’s Inn’s new worship space. Included in these documents are lists of who participated in the service, where the participants stood, kneeled, or sat and when, what they said and did, and to some extent what they thought about what was happening at the time and in the subsequent days and weeks that followed.

Our goal in this website is to make this material available, as well as to consolidate the things we have learned from it about the architecture of post-Reformation worship spaces as well as the use in concrete situations of the worship services scripted by the Book of Common Prayer. Our purpose here is to make this material available, together and in accessible form, to contribute to a broader discussion about the conduct of worship in post-Reformation England.

As Judith Maltby has justly pointed out, religious historians’ fascination with the theological debates that continued to divide people one from another in post-Reformation England while they entertained the learned elites and their concern with the “spiritually disgruntled” in early modern England has obscured the extent to which use of the Book of Common Prayer provided the basic framework for English worship and spiritual formation after 1559 in parish churches, chapels, and cathedrals across the country.[2] The material provided here demonstrates that by 1623 use of the Prayer Book was sufficiently familiar, customary, and expected that its use in the consecration of Trinity Chapel was fluid and coherent, the newly-constructed building was clearly designed to accommodate its particular spatial requirements, and the modifications to the regular order of “Divine Service” to make this event into a ceremony of consecration were done in an informed and appropriate manner. The designers and performers of this ceremony clearly knew what they were doing and how to do it effectively; their actions were based on the experience of common practice and a clear understanding of what they were doing.

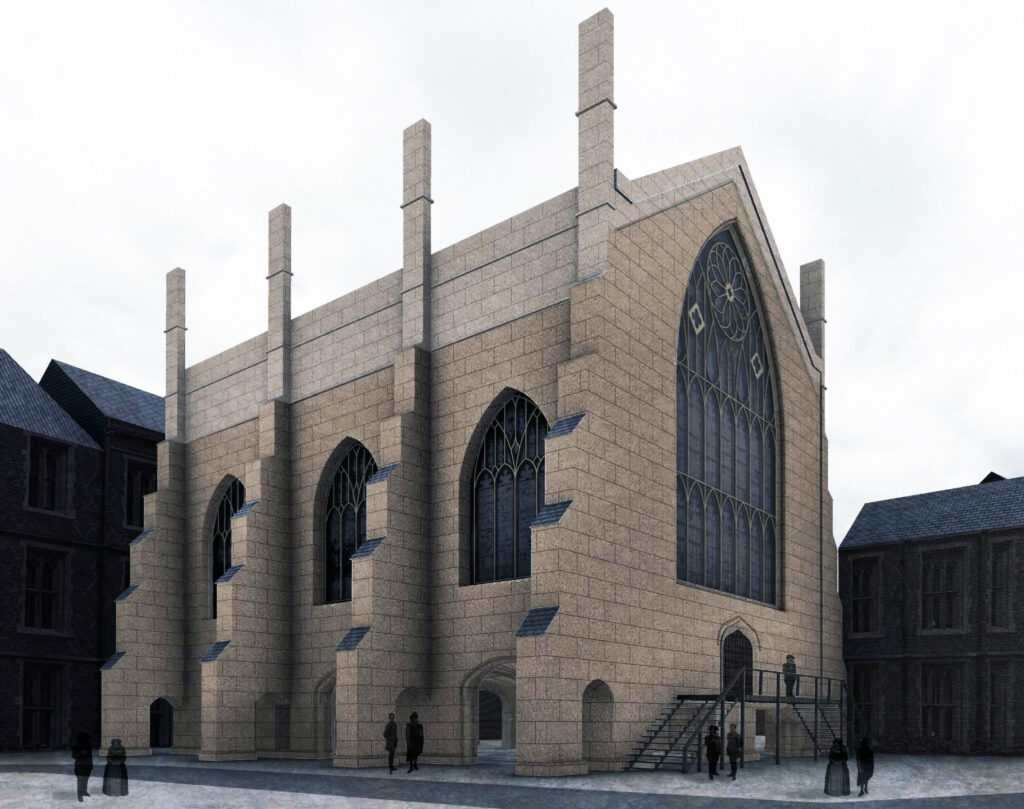

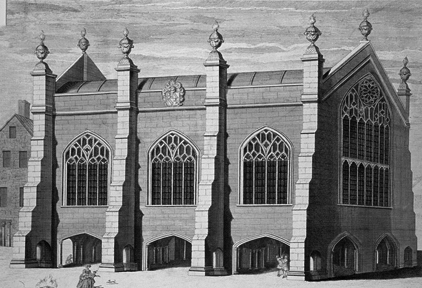

In this introduction, we will sketch out the kinds of information contained in the various appendices, enabling our readers to understand what they now have available. This material includes various visual and written records of the Chapel and its Dedicatory Service as well as a reconstruction of Trinity Chapel’s original floor plan. The fabric of Trinity Chapel itself provides part of the visual record (go here for a discussion of Trinity Chapel in its original design and the changes made in it over the past 400 years), since one of its stained glass windows contains an image of the Chapel itself.

This image shows[3] the building itself as well as the act of transferring the keys to the structure from the builder to the Treasurer of Lincoln’s Inn, an act he would repeat at the beginning of the Consecration service, this time handing the key over to George Montaigne, Bishop of London.

An image of Trinity Chapel from the mid-1700’s shows us another view of its original external appearance. The bill for carpentry and woodwork done in the Chapel by Price the Joiner provides clues as to furnishings that enable us to reconstruct the building’s original floor plan and note similarities and differences between the layout in 1623 and the layout today, go here. An image of another portion of the Chapel’s original windows records John Donne’s contribution to the Chapel’s construction.

Perhaps more important, Latin manuscripts in the Archives of Lincoln’s Inn provide us two full and independent accounts of what happened at Trinity Chapel between 8:00 and 11:00 on May 22, 1623 in almost minute-by-minute detail. George Montaigne’s officially notarized document of consecration gives us an outline of the actual worship service, the names of the participants, and the process of its performance. This outline is filled in with an even fuller account by a resident of Lincoln’s Inn, including the special prayers and ceremonies incorporated into the regular order of Divine Service for this occasion.

The ceremony itself was very well attended, according to a letter from John Chamberlain to Sir Dudley Carleton. Chamberlain’s letter reminds us of the aftermath to the ceremony at Trinity Chapel, which included the preservation of sermon notes and the publication of Donne’s sermon preached as part of the cermony, as well as suggesting how the occasion was interpreted by those unhappy with Prince Charles’ plans – then unfolding — to marry a Spanish princess.

When one adds to this store of information the rites of the Book of Common Prayer of 1604 and the text of the sermon John Donne preached on this occasion and published shortly afterwards with the title Encaenia, The Feast of Dedication,[5] one has a remarkably complete record of the proceedings, a record so sadly lacking for most occasions of worship in Elizabethan and Jacobean England.[6] These documents reveal that by the early years of the seventeenth century and after a half-century of practice, clergy and laity in the Church of England were sufficiently familiar with the rites of the Book of Common Prayer to perform them easily, as one does something with which one is highly familiar and thus able to adapt skillfully and effectively to make possible the observance of specific occasions not provided for by the Prayer Book itself.

During the course of the commencement of the basic rites of morning worship on Holy Days and Sundays ( Morning Prayer, the Great Litany, and Holy Communion) for Trinity Chapel, the Bishop of London and his staff added well-crafted prayers to make this service into a Service of Dedication and Consecration, setting aside this new worship space from a common to a holy purpose, “for . . . worship, the building up of the living, and the remembrance of the dead.”

Lincoln’s Inn built a chapel to house effective use of that Prayer Book, built, as Donne put it in his sermon, for “the Common Prayer of the Church,”[7] adopting the two-room model used since the early days of the English Reformation to enable Prayer Book worship to take place in medieval buildings, with the Service of the Word taking place in the nave and the Service of the Table taking place in the Choir or Chancel. Here, there is a space for the Word and a space for the Table; by putting the pulpit in the center of the nave, they effectively balanced Word and Table rather than overshadowing the table with the pulpit as in Reformed churches.

The design of Trinity Chapel — combining a two-room model for structuring in space as well as in time the two great acts of Christian worship — the hearing of the Word and the shairing of bread and wine — together with a neo-Gothic building design and a return to the use of stained glass windows locates Trinity Chapel at a turning point in the development of post-Reformation English worship. Continuing on the one hand the restructuring of sacred space heralded by the Book of Common Prayer of 1552 and embracing on the other the use of visual evocations of the sacred, Trinity Chapel represents at once the embodiment of Cranmer’s mature understanding of worship as corporate action and the coming enrichment of English worship through the recovery of visual manifestations of the sacred.

The Bishop of London and his staff were able to choreograph effectively use of the Prayer Book in an unfamiliar locale and to modify its ceremonies gracefully to fit the particular circumstances provided by the inauguration of Trinity Chapel as a site of worship. The ceremonial for this event effectively articulates relationships between laity and clergy and between the local chapel, neighboring parish churches, and the Bishop of the Diocese, making the occasion not only the inaugural service of worship in Trinity Chapel but also a lesson in the piety, ecclesiology, and polity of the Church of England.

[1] At least for the moment, anyway. The standard description of worship in early modern England is William Harrison’s account in his Description of England, ed. Georges Edelen (New York, Dover, 1994), pp. 33-34.

[2] See her Prayer Book and People in Elizabethan and Early Stuart England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), throughout, but esp. pp. 1-30.

[3] Use of stained glass in the original design of Trinity Chapel is itself testimony to early Stuart developments in English religious sensibilities and concepts of holiness.

[4] Presumably to Bishop Montaigne by a representative of Lincoln’s Inn, as described in the documents discussed below. The man receiving the key is not dressed in distinctive religious garb, however, so it is possible either that the Bishop of London had not yet put on his clerical vestments at that point in the ceremony, that the scene depicts the handing over of the key from the builder to a representative of Lincoln’s Inn rather than to Bishop Montaigne, or that the person making the stained glass window did not have specific instructions about how to garb the people in the image. Just because the evidence is contemporary with the event does not make it self-interpreting.

[5] John Donne, “Encaenia. The Feast of Dedication,” in The Sermons of John Donne, ed. George Potter and Evelyn Simpson(Berkeley, CA, 1959), vol. IV, pp. 362-379. The text of this sermon is also available online here: http://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/cdm4/document.php?CISOROOT=/JohnDonne&CISOPTR=3183&REC=18

[6] And therefore allowing a host of misconceptions, premature conclusions, and flat-out erroneous assumptions to be made for those events. For a much more authoritative account, see Judith Maltby, Prayer Book and People in Elizabethan and Early Stuart England (Cambridge, 1998).

[7] Potter and Simpson, vol. 4, 375.

[8]According to its heading in Fifty Sermons. See Potter and Simpson on the dating of this sermon in volume 2 of their edition of Donne’s sermons, pp. 29–30, where this sermon is printed as #10.

[9]In an inscription Donne wrote in the first volume of a six-volume edition of the Vulgate that he gave to the Inn in February of 1624, Donne says that he laid the first stone “sua manu.”

[10] Here, below an image of St. John, Donne has had inscribed this message, “Io Donne Dec: St. Paul: F : F” (for “Johannes Donne Decanus Sancti Pauli Fieri Fecit,” i.e., “John Donne Dean of St Paul’s caused [this] to be made”) a reminder of his own personal contribution to the building fund (see fig. 2). We are grateful to Diarmaid MacCulloch, Professor of Theology at Oxford, for assistance with the translation of this Latin passage.

[11] We are grateful to the research of Peter Foden and Jo Hutchings, Archivists at Lincoln’s Inn, for information on Donne’s continued association with Lincoln’s Inn after he became Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral. They point out, in notes supplied privately, that, though Donne was appointed Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral in 1921, he retained the title of Preacher at Lincoln’s Inn until 1622, when he was “expressly permitted to keep his chamber.” (Black Books 2:229–230). In November of 1624, however, Donne gave up his chamber, which was then assigned to Eusebious Andrewes, Master of the Bench. (Red Book 1 [E1a1], folio 108r) The Archivists indicate that, regrettably, the location of Donne’s chamber in the Inn has not been determined.

[12] Potter and Simpson, IV, 363.

[13] Wall’s article, “Situating Donne’s Dedication Sermon at Lincoln’s Inn, 22 May 1623,” John Donne Journal 26 (2007), 159-239, examines in detail an array of visual and verbal evidence for the physical arrangements of Trinity Chapel in 1623; readers wishing an extended discussion of the issues summarized here will find it in that article. Careful readers will notice that the floor plan of Trinity Chapel in 1623 provided here differs from the one provided in JDJ in one significant detail regarding the placement of the pulpit. Here, the pulpit is on the main floor of the nave, westward of the screen that helps to separate the chancel from the nave. In JDJ the pulpit is “above the step,” on a level with the communion table and behind the screen. The diagram in JDJ interprets the statement that the pulpit was “in the midst of the chappell in the upper part of the Chappel” to mean that pulpit, like the altar, was “above the step.” Wall has changed his mind, for two reasons. First, even though there was a fad for centrally-located pulpits in England in the early 17th century he has not been able to find an image of one located in the chancel area; all the images he’s seen place the pulpit on the floor level of the nave. Second, in retrospect, he thinks everything else In the design of Trinity Chapel reinforces a clear separation of space as well as function between nave and chancel, a separation that is confused by locating the pulpit in the chancel but reinforced by locating it on the floor of the nave, as shown here.

[14] The steps built to provide access in 1623 (presumably made of wood) were actually replaced in 1624 by a new staircase made of 1, 000 bricks. See Mark Ockelton, A Portrait of Lincoln’s Inn (London: Third Millennium Publishing, 2007), p. 112.

[15] Presumably describing a platform on which the altar stood and on which people could kneel to receive communion.

[16]William Holden Spilsbury, Lincoln’s Inn: Its Ancient and Modern Buildings (London: W. Pickering, 1850), pp. 54-59.

[18] This two-room design represents continuation of tradition in England and resistance to the contemporaneous design of buildings for reformed worship emerging in Scotland and elsewhere in which space is organized into a single room with pews facing eastward toward a large pulpit standing just in front of the east wall, with a small communion table located at the base of the pulpit, on the westward side of the pulpit. Interestingly, the two-room model for churches in the Anglican tradition has been revived in some contemporary post-Liturgical Movement churches; see for example St Gregory of Nyssa, San Francisco.

[19] In terms of architectural style as well as internal layout, it should be compaired with the Queen’s Chapel designed by Inigo Jones and built at St. James’ Palace beginning in the spring of 1623, a chapel originally intended for Catholic worship by Charles’ Spanish princess whom lots of folks in May of 1623 thought would soon be his wife. We will return to this point later in this essay.

[20] Probably in the late seventeenth- or early eighteenth-centuries, when the east end of the building needed to be rebuilt due to faulty workmanship in the original construction.

[21] The Records of the Honorable Society of Lincoln’s Inn [Black Books], ed. W. P. Baildon, R. Roxburgh, and P. V. Baker, 6 vols. [London: Lincoln’s Inn, 1897-1968), 2:197.

[22] Chamberlain, “Letter to Carleton, 30 May 1623, in The Letters of John Chamberlain, ed. Norman Egbert McClure, 2 vols. (Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society, 1939) 2:500.

[23]The standard account of the revival of consecration ceremonies in the Church of England is that of J. Wickham Legg, English Orders for Consecrating Churches in the Seventeenth Century, Henry Bradshaw Society, 41 (London, Harrison and Sons, 1911). Ridley on this subject is quoted from Legg, p. xviii. Legg includes the consecration of Trinity Chapel in his list of 17th century consecrations, but he does not seem to have had access to the documents from the Lincoln’s Inn archives we make available in this study.

[24] Legg also discusses these services in both the style and the perspective of the early 20th century, with its developing conversations about recovering the Church of England’s catholic liturgical heritage provoked by Ritualism’s emergence from the Oxford Movement. This material cries out for discussion from the perspective of the 20th century’s Liturgical Movement and the discussions that led to the Book of Common Prayer of 1979 and, especially, the Book of Occasional Services of 2003, with its extensive array of rites of consecration.

[25] Legg believes that there was on some occasions a desire to perform all the public rites of the church, including baptisms, confirmation, marriages, ordinations, and funerals, but these ambitious plans seem rarely if ever to have been realized. See Legg, xxxiiii.

[26] See Legg, p. xxviiii.

[27] In his article “Consecrating Lincoln’s Inn Chapel,” in John Donne Journal 23 (2004), 139-160. Johnson’s style of referring to the service at Trinity Chapel on May 22, 1623 as a Consecration service is slightly misleading, however, because it implies that the entire service conducted between 8:00 and 11:00 on the morning of May 22nd was a distinctive liturgical rite, whereas it actually consisted, as we will see, of the standard Prayer Book rites for morning worship on a Holy Day, augmented by prayers and the reading of documents that perform the act of consecration. For the rite, see Legg, pp. 1-8.

[28] What the officials of Lincoln’s Inn are doing, in effect, is handing over ownership of the Chapel to the Church of England by transfer of the means of access to the building to its official representative in London.

[29] Bishop Montaigne’s document at this point in its account of the event notes the Bishop’s special regard for the fact that the members of the inn had caused Trinity Chapel “to be newly now erected, built, and constructed, using their own personal expenditures, and have sufficiently and suitably decorated and fitted out with sacred table, pulpit, suitable seats, even a bell.”

[30] Lines based on BCP texts, especially the General Confession, the Prayer of Humble Access, and the post-communion prayer

[31] The Psalm was presumably sung in English, either to Anglican Chant (in the Great Bible translation) or in the translation of Sternhold and Hopkins, sung to the tune provided in such editions as STC 2073. Given that Anglican Chant in this period was used primarily by choirs and there is no record of the Chapel at Lincoln’s Inn having a choir (nor is there any indication that the other Psalms read in this service were sung), we believe the setting and translation were those of Sternhold and Hopkins. For this setting of Psalm 23, see the end of this document.

[32] For an account of Donne’s career at Lincoln’s Inn that sees Donne occupying comfortably a place in a “Calvinist conformist” tradition of “evangelical preaching,” at Lincoln’s Inn and sees Trinity Chapel as essentially “an evangelical theatre for preaching,” see Emma Rhadigan, “Donne’s Readership at Lincoln’s Inn and the Doncaster Embassy,” in The Oxford Handbook of John Donne, ed. Jeanne Shami, Dennis Flynn, and M. Thomas Hester. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), pp. 576-88.

[33] After all, with both the Bishop of the Diocese and the Dean of the diocesan cathedral present for this service, one can have no higher authority for liturgical experimentation.

[34]“Encaenia” is a Greek term meaning roughly “occasion of commencement,” or “renewal,” or “dedication,” The word is found in the Greek text of the passage from John’s Gospel (10:22) Donne chose as his text for this sermon, translated in the printed text as “Feast of the Dedication.” Donne or his auditors at Lincoln’s Inn would perhaps also have known this word from its use at Oxford University as the name for an annual ceremony held on the Wednesday of the ninth week of Trinity (spring) Term at which the University awards honorary degrees and commemorates its benefactors. This link seems appropriate since part of what Donne does in this sermon is to recognize members of Lincoln’s Inn for their role as benefactors of Trinity Chapel.

[35] Using the collective “We” to include himself in the company—appropriate since Donne had until recently been one of them, Preacher to Lincoln’s Inn, before taking his current job as Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral, and still in 1623 retained his rooms in the Inn, not giving up that tangible sign of membership in the Inn until 1624.

[36] Preparation for celebrating Holy Communion for Bishop Montaigne would include 1. making sure that the altar had a “fair linen” cloth on it, 2. putting the communion cup and a plate upon the altar together with sufficient wine and bread for the communion, and 3. putting on a cope, as was customary practice in St. Paul’s Cathedral. The text refers to preparation here at the beginning of the rite and also later, after the reading of the Epistle and Gospel, where we are told he “girded himself for the Lord’s supper.” One would of course like to know what he did and when, though “the reference to “girding” may suggest that this refers to his putting on his cope before reciting the prayer over the elements.

[37] Again, “jurisconsults”

[38] Presumably because George Montaigne was a mountain of a man who needed a rest after the exertions of the day, especially the exertions of parading around a building that measured 40×60 feet. The Bishop’s version of this moment tells us that “there for a little while we rested ourselves, then, with the population settled, and the noise settled down, we proceeded.”

[39] See Appendix 9, p. xx.

[40] For a detailed account of the strange matter of the Spanish Match, see Glyn Redworth, The Prince and the Infanta: The Cultural Politics of the Spanish Match (New Haven: Yale U.P., 2003). For a discussion of the Spanish Match in the context of James I’s concern for Christian unity in Europe, see W. B. Patterson, King James VI and I and the Reunion of Christendom (Cambridge: C.U.P., 1997), pp. 293-364. For other discussions of the Spanish Match, see J. H. Elliott, The Count-Duke of Olivares: The Statesman in an Age of Decline (New Haven: Yale U.P., 1986), Thomas Cogswell, The Blessed Revolution: English Politics and the Coming of War, 1621-1624 (Cambridge: C.U.P., 1989) and the essays on the subject in Alexander Samson, ed., The Spanish Match: Prince Charles’s Journey to Madrid, 1623 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006) and Michael Questier, ed., Stuart Dynastic Policy and Religious Politics,

1621-1625, Camden Fifth Series (Cambridge: C.U.P., 2010).

[41] Ludovick Stuart, second Duke of Lennox and first Duke of Richmond

[42] Lionel Cranfield, first Earl of Middlesex

[43] James Hamilton, 2nd Marquess of Hamilton and 4th Earl of Arran KG PC (1589 – 1625)

[44] Thomas, First Lord Arundell of Wardour (1560-1639), a Catholic who was named Lord Arundel by James I in 1605.

[45] George Calvert (1579 – 1632), Secretary of State under James I, lost power over support for the Spanish Match, later supported creation of colony of Maryland as a haven for English Catholics.

[46] Don Carlos Coloma

[47] George Montaigne

[48] So much so that at the trial of William Laud by the puritans in 1641 the presence of stained glass windows in Trinity Chapel (including the one with Donne’s name in it) was listed among the charges brought against the Archbishop.

[49] This of course became true in churches in the reformed tradition as well; Wall grew up in an exceptionally austere Southern Presbyterian church which sported a complete set of stained glass windows installed from the late 19th to the early 20th centuries. The Presbyterian forebears of the people whose names are inscribed in these windows would have gleefully smashed them into shards.

[50] For a fuller discussion of the interior of Trinity Chapel and its renovations, see my essay “Situating Donne’s Dedication Sermon at Lincoln’s Inn, 22 May 1623,” in John Donne Journal 26 (2007), pp. 159-219.

[51] We have often wondered if Cranmer, who knew a great deal about the Church Fathers, also understood the distinctive organization of patristic liturgy, anticipating the Liturgical Movement by some 250 years.

[52] For a discussion of the placement of pulpits, and its meaning, see Wall, “Situating Donne’s Dedication Sermon,” pp. 212-15.

[53] Maltby, especially pp. 1-30.

[54] Harrison, p. 34.