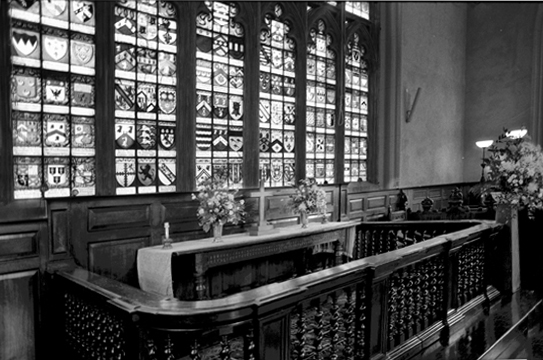

The example of Trinity Chapel, a work of new construction in 1623, when relatively few new churches were being built in England, as well as a building that combines medieval design with liturgical arrangements that reflect the needs of the then-current Book of Common Prayer (1604) suggests the complexities of English religious life in the early seventeenth century. Simultaneously looking backward to the Middle Ages in its outward design and seeming to embrace a Laudian concern for the beauty of holiness in its use of stained glass windows, Trinity Chapel also establishes itself in the location of its altar and pulpit at the heart of the English Reformation’s emphasis on worship that is corporate, liturgical, and sacramental.

Through his involvement in the design and construction of Trinity Chapel, John Donne located himself at the heart of this complex moment. As Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral, he worshipped daily in a space that had already returned its altar to the place it stood before the Reformation, yet here he supported personally and financially a building seemingly dedicated to continuing worship as Thomas Cranmer, by 1552, had envisioned it.1 Eventually, of course, those responsible for worship in Trinity Chapel would follow the pattern set by the cathedral; they got rid of the long bench that Hugh Price had so carefully constructed against the east wall of the Chapel and replaced it with a table in the traditional position of an altar and railed it in, the arrangement that persists today.2

The way we interpret complex developments such as these in the religious life of early modern England is, of course, often shaped by the presuppositions we bring to these questions. Where we stand often shapes what we recognize in the past, and how we label it, and therefore what value we place on it.3 There is a vast amount of data — both textual and material — that comes down to us from the past, vastly more than anyone can fully comprehend. One needs structures, priorities, and concepts that set limits and prioritize one’s attention.

Scholarship

One way in which historical scholarship has proceeded in these matters is through one generation’s recognition of the limits of the previous generation’s work. Often, one has the suspicion that scholars are reading the same words, only using different dictionaries. For instance, historians in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries who embraced the rise of Anglo-Catholicism yet grieved the difficulty that Anglo-Catholics had in being affirmed by the Church of England’s establishment found in the first Book of Common Prayer (1549) a version of worship in English that they could affirm; recognizing this, they sought to play up continuities with the Medieval Church and play down the differences.

Diarmaid MacCulloch, perhaps the most distinguished church historian of our time, has admitted that his efforts to remind us of the extent of the differences between the pre- and post-Reformation English Churches and to document the influence of the Reformed movement in the European Reformation were inspired by his recognition of how much data the Anglo-Catholic historians were ignoring. Eamon Duffy, recognizing that most English church historians were Anglicans who took the Reformers’ side against the medieval Church, has made his career on recovering the character of that Church and on reminding us of the experiences of the English who remained loyal to the Papacy.

Other English historians, more drawn to English Puritanism, and, perhaps, to the connections between various Puritan groups and their modern denominational descendants, find Puritans everywhere, in spite of effective counterarguments posed by scholars such as Ian Green, who in his monumental study Print and Protestantism in Early Modern England documents both the differences between mainstream writers on the spiritual life and their Puritan contemporaries and the difficulty some scholars have in recognizing that distinction.4 Of Alec Ryrie’s Being Protestant in Reformation Britain,5 one reviewer pointed out that it seems better titled Being Puritan in Reformation Britain.

The Liturgical Movement

Often, one has the suspicion that scholars are reading the same words, only using different dictionaries. In this context, I need to define my own perspective on the data and on the issues raised by that data in our effort to understand more fully the English Reformation and its aftermath. My perspective is shaped by my experience as both scholar and Episcopal priest, as one engaged both with the cognitive framework and the performative principles of the Liturgical Movement, which had a profound effect on changes of worship in liturgical churches in the latter part of the 20th century.

The Liturgical Movement began among Roman Catholics in Europe in the late 19th century, then spread to England and to the United States in the 20th. Its implications have had significant consequences for worship in post-Vatican II Catholicism, in the Episcopal Church’s thorough-going revision of the Book of Common Prayer in the 1970s, and in revisions of their Books of Common Prayer in many other churches of the Anglican Communion.

Scholars involved in the Liturgical Movement have looked backward at the history of Christian worship, especially to the Age of the Church Fathers, and outward, especially concerned to implement in contemporary practice what they found in their explorations of early Christian worship. Their special concerns have been to recover an understanding of the Eucharist as the central activity of Christians as they gather, to emphasize that celebration of the Eucharist is a corporate activity in which all those gathered, lay and ordained, have their roles to play, and that reception of the Bread and Wine of Communion is an essential part of the corporate action.

Scholars in the Liturgical Movement researched the history of Christian worship, using patristic and biblical studies, early liturgical texts, and archaeological work on early Christian worship sites. One of the most important outcomes of the Liturgical Movement is a book written during World War II by an Anglican Benedictine monk named Gregory Dix called The Shape of the Liturgy. Dix recast questions about the meaning of Jesus’ words about his presence in the Bread and Wine of Holy Communion away from spatial terms to temporal terms. That is, while traditionally Jesus is discussed as being present in relationship to the consecrated bread and wine, apart from the gathered congregation, to be adored, and occasionally received, by them, in Dix’s view, the language of “presence” becomes meaningful through the actions of the celebrant and congregation together, as they offer, bless, break, and receive the elements of bread and wine.

In current usage, for example, after the consecration clergy and congregations join in using language drawn from St Augustine’s Homily 272 <https://enlargingtheheart.wordpress.com/2013/07/20/augustine-of-hippo-you-are-the-body-of-christ-and-its-members/>. The priest declares, “The Body of Christ for the Body of Christ. Behold what you are.” and the congregation responds, “May we become what we receive.”

Cranmer’s Liturgical Movement

This might seem to be a way of discussing the meaning of the Eucharist far removed from Cranmer and the mid-sixteenth-century Church of England. In fact, Dix was strongly critical of Cranmer’s liturgical skills, chiefly because he believed that Cranmer had not fully embodied the patristic four-fold action of consecration in his 1552 version of the Communion service. But, consider this: 1. Cranmer and his colleagues also drew heavily on the Church Fathers, and especially on St Augustine to support their Reformation. 2. Cranmer also emphasized making worship accessible by creating worship texts in the vernacular and by making worship corporate and interactive by drafting portions of his liturgies to be spoken by the celebrant and the congregation either corporately or by turn-taking. 3. Cranmer emphasized reception of the bread and wine of communion, insisting that there would be no celebration of communnion by the priest alone. 4. Cranmer’s Eucharistic liturgies explain themselves by emphasizing the language of full participation; it is by taking part with the celebrant in the full action of offering, blessing, breaking, and receiving that we are assured “therby of thy favour and goodnes towarde us, and that we be very membres incorporate in thy mistical body, whiche is the blessed company of al faithful people, and be also heyres through hope of thy everlasting kingdom.” One even finds use of the fourfold action of consecration in one of the Catechisms published in the years following the Elizabethan Settlement. 5. Cranmer called for use of what we would, today, call free-standing altars where the celebrant would stand on one side of the table with his parishioners around the opposite side. 6. Cranmer placed the congregation’s reception of the bread and wine of communion at the center of the Eucharistic action. 6. Cranmer also insisted that baptisms be conducted as part of the parish community’s weekly worship, emphasizing anew his understanding of worship as corporate, communal, and sacramental.

From this perspective, Cranmer clearly expected that worshippers using his Prayer Book would participate fully in the Eucharist at least weekly, on Sundays, and additionally on other Feast or Saints’ Days during the Church Year. True, he was a man of his age in that he placed too much emphasis on St Paul’s warnings about receiving communion unworthily; see his Exhortations about reception of Communion in which warnings against unworthy reception outweigh encouragement to receive by a score of two to one. Combining that lesson with the inherited weight of medieval memory about the rites of penitence one had to go through before reception suggests why it took the government’s passing laws to enforce reception of communion at least three times a year, as well as why it has taken 400 years for full participation in all aspects of the Eucharist to become a general expectation of those in attendance. At least, with the use of Cranmer’s Prayer Book, the Church of England still observed the cycle of the seasons, the discipline of biblical readings guided by the Lectionaries, and the emphasis on corporate, participatory worship. With the observance of the rite of Holy Communion each Sunday and Holy Day at least through the sermon and the prayer for the Whole State of Christ’s Church, the opportunity for full participation in the rites of Christian identity was there, and the reminder of it was there, whether people took advantage of it or not.

The process of liturgical change, especially in the Episcopal Church after the introduction of the Prayer Book of 1979, replicated in so many ways the transition from medieval worship to the use of Prayer Books after 1552. There was the transition in language — in this case, among other changes, from early modern to fully modern English — as well as the transition in use of space, from altars against the east wall with clergy facing eastward during the Eucharistic prayer to free-standing altars with clergy facing westward facing their congregations, and transitions in congregational participation, from congregations participating some to congregations participating more (now reading lessons and intercessory prayers and helping with the distribution of the bread and wine of Communion). To this student of liturgical change, the similarities are uncanny, the possibilities they provide for interpreting Cranmer’s understanding of what he was about in the reign of Edward VI compelling.

Then and Now

Of course, dramatically different mental frameworks separate us from the 15th and 16th centuries. Theirs was a time in which religious traditions were either right or wrong, either the Body of Christ or the Antichrist. Yet, while we are more or less comfortable with, or at least, more tolerant of, religious pluralism, we still miss the nuances of faith, the ways in which theological issues — such as the extent of human limits and the benevolence of God, or the relationship between Christ and Christ’s followers in the Eucharist — in the age we study.

The consequences of the Reformation played out in unexpected ways. While Catholicism became increasingly authoritarian, those engaged in reformation splintered, and splintered again into the literally hundreds of Protestand denominations we encounter today. Along the way, they drew back from congregational involvement into investing the minister with increasing authority. Puritans objected to the Prayer Book’s investment of voice in the congregation; worship became increasingly focused on preaching, on the charismatic minister, often devolving into a personality cult structured around him. Engagement with the rite of Communion has shrunk to the point of its irrelevance, a service occasionally tacked onto the end of a preaching service.

Of course, all the simple distinctions we in our time inherit from the Reformation — the either/or thinking that defines Catholic from Protestant — have been scrambled in our time. We live in an age in which long-standing distinctions between Catholics and Protestants have dissolved. Everyone worships and reads the Bible in the vernacular. Sunday worship includes preaching and the Eucharist. Catholics and Lutherans have agreed on their understandings of faith and Catholics and Anglicans have agreed on the meaning of the Eucharist in a document in which the word “transubstantiation” appears only in a footnote.6 Distinctions now seem almost more about the rhetorical usefulness of having an “other” to define oneself over against than they are for promoting mutual understanding.

Role of the Virtual Donne Websites

The Virtual Donne website, in its component parts, seeks ways to enable us to experience the lived religion of the English in the years between the Elizabethan Settlement of Religion in 1559 and the English Civil War. While acknowledging the fact that the Elizabethan Settlement provoked opposition that would ultimately contribute to the outbreak of the Civil War, we seek to shift attention from theological debates to the experience of worship. The learned side of the faith was, after all, more the province of the learned and the powerful than they were of the vast majority of folks, who were enabled to gather in community, to be supported and recognized in life’s transitions, and to find language to give voice to their deepest experiences of life by the use of the Book of Common Prayer. It was, of course, use of the Prayer Book that survived, pretty much unchanged, into the present day, long, long after debates about transubstantiation, or predestination, or what kind of faith actually justifies had faded away into obscurity and the provenance of the specialist.

- Kenneth Fincham and Nicholas Tyacke encapsulate seventeenth-century developments in English religious life neatly in Altars Restored: The Changing Face of English Religious Worship, 1547-c1700 (Oxford, 2007).

- Finding a table here caused me to wonder if it were the table Hugh Price built for the Chapel in 1623, but, unfortunately, this table seems to have been acquired by the Inn in the 2oth century.

- An approach that leads to books from conflicting perspectives, see Diarmaid MacCulloch’s All Things Made New:The Reformation and Its Legacy (Oxford, 2017) and Eamon Duffy’s A People’s Tragedy (Bloomsbury, 2021).

- See Green’s Print and Protestantism in Early Modern England (Oxford, 2000), 304-71.

- Alec Ryrie, Being Protestant in Reformation Britain (Oxford, 2013.)

- Click here: <https://www.prounione.urbe.it/dia-int/arcic/doc/e_arcic_eucharist.html>