The Building over Time

The service of worship conducted in Trinity Chapel on May 22, 1923 was the service of consecration, or dedication, as Donne labels it in his sermon, the first service conducted in this space, a new space just completed for the use of members of Lincoln’s Inn. The Black Books of Lincoln’s Inn show that the Inn had been planning for this day for several years. Donne preached at this service because he had been involved in the project since early in his tenure as Reader, or Preacher, at the Inn.

Donne went to work at Lincoln’s Inn 1616 and remained in this position until he became Dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral in 1621. His activities in support of the building of Trinity Chapel included preaching a sermon at the Inn, in 1618 or 1619,specifically to support the residents of the Inn in “preparing . . . to build their Chapel.”[8] He also, according to his own testimony, laid the first stone of the Chapel “with [his] own hands.”[9] In addition, he contributed to the cost of one of the stained glass windows, a fact which to this day is recorded in the window itself (Appendix 7).[10] The Inn’s leadership, perhaps in appreciation for his active role in the construction of Trinity Chapel, invited Donne back from his work as Dean of St. Paul’s to preach the sermon at the service of dedication and consecration for this building on 22 May 1623.[11]

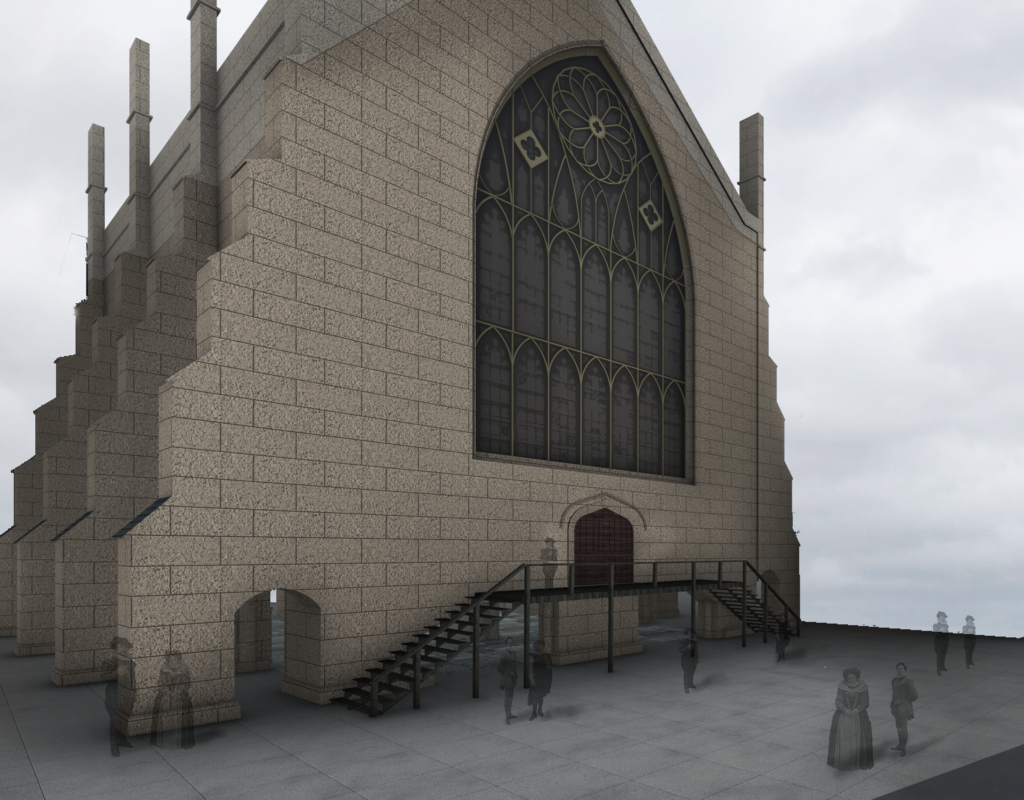

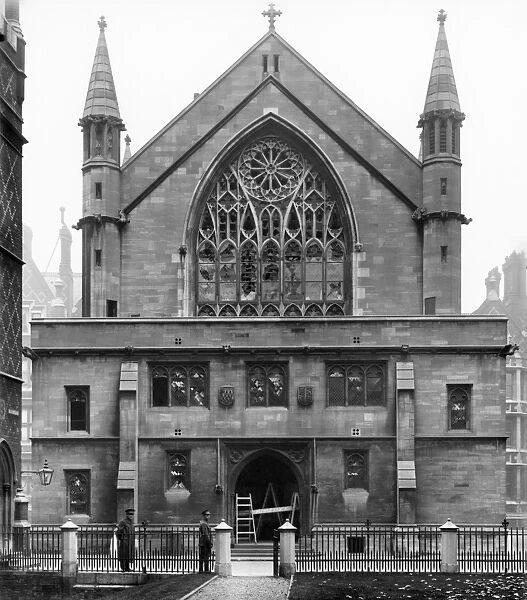

Trinity Chapel — unlike Paul’s Cross and St Paul’s Cathedral — still stands today on the leafy and tranquil grounds of Lincoln’s Inn, looking from the sides, from the east end, and from underneath much as it did when it was built in the early 1620’s. Images of the building through the years — see the inventory below — show a rectangular, highly symmetrical gothic structure approximately 40 x 60 feet in size with large windows in the east and west fronts and 3 smaller windows on each of the north and south sides.

Legend has it that Trinity Chapel was designed by Inigo Jones, an origin story unlikely on the face of it, given Jones’ disregard for medieval architecture in his revisions to St Paul’s Cathedral in the 1630’s. The strongest candidate for the designer of Trinity Chapel is John Clarke, an Oxford stonemason who actually built the building.[1]

Unlike St Paul’s, however, Trinity Chapel escaped the Great Fire with its original design intact. Historic record shows that the original wooden steps on the Chapel’s West Front were replaced in the mid-1620’s by a set of brick steps. Later in the 17th century, the East Front collapsed and had to be rebuilt. Only the west end – extended by about 25 feet in the late 19th century – embodies significant change in the Chapel’s original design.

Even here, the basic style of the original building was closely followed in the design of the extension, especially in the windows on each side of the building’s extension. The most significant change is presented in the newly-designed West Front, with its more elaborate entranceway that encloses the main entrance and incorporates a pair of staircases to replace the original design’s free-standing steps[14] leading up to a large doorway in the west end.

Because of the importance of Lincoln’s Inn as an Inn of Court, the appearance of Trinity Chapel as documented over the years by a series of images, beginning, of course, with the image of the Chapel in one of the building’s stained glass windows, an image that documents not only the building but one of the events of Ascension Day, 1623, the transfer of the keys to the Chapel from the builder to the Treasurer of Lincoln’s Inn.

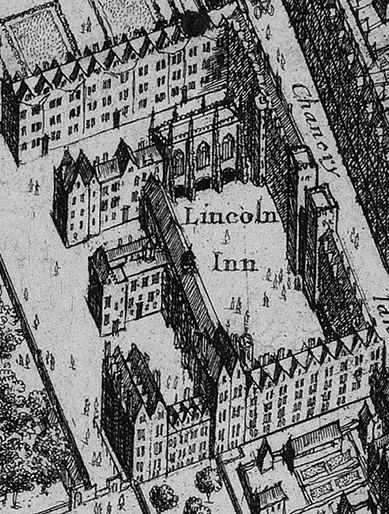

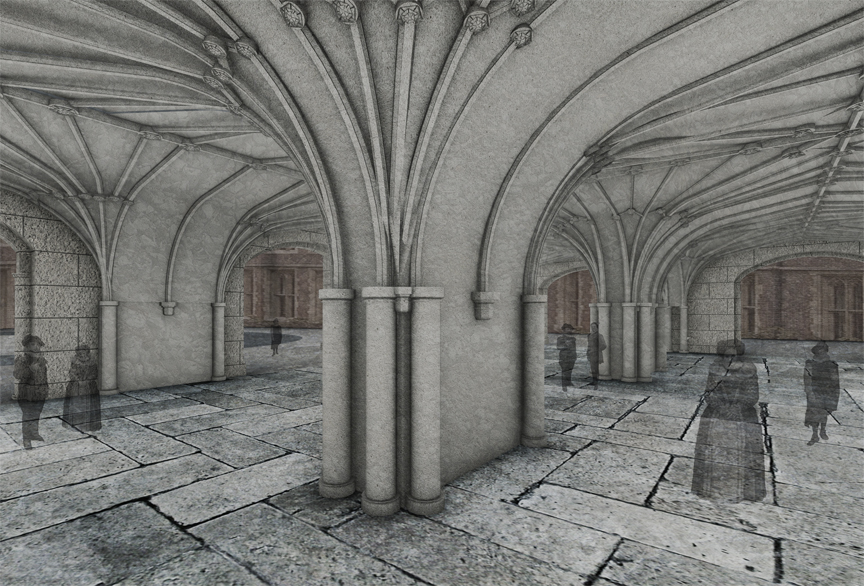

Some 40 years later, Trinity Chapel appears in Wenseslaus Hollar’s Map of West London (see above detail) in a depiction that agrees in essentials with the version of the building shown in the previously-displayed stained glass window. Worth noting at this point is the striking design of the building’s undercroft, a space intended for use as a cemetery for members of Lincoln’s Inn, a purpose long since discontinued.

By the eighteenth century, the Inn’s history of the Chapel recounts, the Chapel’s undercroft had become known as a place where mothers unable to look after for their newborns would leave them in the care of the Inn. The Inn found homes for them, having given them the surname Lincoln.

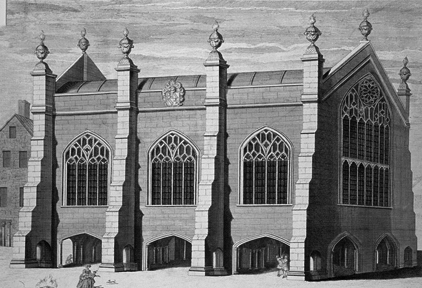

In George Vertue’s engraving of the Chapel from 1730, seventy years after Hollar’s depiction, it seems that the only major change in Trinity Chapel in the intervening years was the replacement of the triangular structures on the top of each vertical pillar with a more urn-like structure.

This urn-like design might be taken to be a reflection of artistic license rather than of accurate depiction were it not for the fact that this feature is also included in a painting of Trinity Chapel from roughly the same period of time (see below).

In any case, by the early 19th century, it seems that all traces of these column-topping structures had simply disappeared, as revealed in these two engravings from the first half of the century.

This absence of column-topping structures continued to at least the end of the 19th century, as attested to by this painting that includes at its left side an image of Trinity Chapel’s east end.

Nevertheless, by early in the 20th century a pyramidal structure reminiscent of its 17th century original was added to the tops of these structural columns, where they stand today.

The simplest version of these structures is found atop the columns on the sides of Trinity Chapel.

A slightly more elaborate version sits atop the columns on the East and West Fronts. In this image, one can see the difference between the color of the stone in the rightmost bay of the building and the color of the stone in the 3 other bays, marking the point at which an additional bay was added to Trinity Chapel in the 19th century.

Unlike so much of early modern London, Trinity Chapel remains today a significant part of the community life of Lincoln’s Inn. With its close connections to, and material traces of, John Donne’s tenure as chaplain, it is well worth a visit.

[1] . See Mark Ockelton, in A Portrait of Lincoln’s Inn, ed. Angela Holdsworth (London, 2007). pp. 108 – 115.